|

|

|||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

The Fragale Family in Escanaba

I did, however, know my great-grandmother Emma Fragale. When I was We moved to southeast Wisconsin about 1962, and after that no visit to my grandparents in Escanaba and Ford River was complete without making the rounds to see grandma Fragale and aunt Harriet. Grade school and high school passed, and then during the 1980's all of those old ladies in Escanaba passed too. In 2001 I moved to New Mexico, but before leaving I spent several afternoons at my parent’s house going through old photo albums, copying many prints onto film and taking notes. My mother had saved Emma’s photo album, Harriet’s photo album and, of course, her own mother Margaret’s albums. In 2007 I finally got around to trying to organize the images. What started out as a project to make a digital album soon grew into a website, and over the following years it became an all-out investigation into my family genealogy. The Escanaba photos were most fascinating to me: Mike and Emma Fragale’s wedding photos, beautiful photos of their three young daughters, and pictures of brothers and sisters from Germany and Italy. There were names from my mother’s memory, like Ewald, and Gusty, and Angelo and Kennett Square. The project expanded to other branches of the family in Ohio, Arkansas, Kentucky and elsewhere, but it’s now come back to Escanaba, to Mike Fragale who immigrated from Italy, and Emma Leisner whose family immigrated slightly earlier from Germany. Michigan’s Upper Peninsula had many German immigrants, but very few Italians, so Mike Fragale’s story intrigued me. What on earth brought a poor teenager from rural southern Italy (a kid who might have never seen snow before!) to settle in Escanaba Michigan, so far from his family? From the bits and pieces I‘ve gathered, here is the story of a man who I almost knew, and the story of his family.

The Fragale NameMy great-grandfather was born Michele Fragale, and we imagined the Italian pronunciation to be frah-gah-lay, with the accent on the middle syllable. Our family always pronounced it fray-gul, and somewhere along the line the spelling changed to Fragile. The first instance of this spelling I know of is in the 1930 U. S. census. The three daughters used the Fragile spelling for their entire lives after that, but the youngest, my grandmother Margaret, wanted the traditional spelling on her gravestone. Mike had no formal education, and Emma only got through the second grade. The only signature of Mike’s I’ve seen, on his WWI draft registration card, had the Fragale spelling. It’s interesting that Mike’s brother Angelo had the same misspelling of the family name in the 1940 U. S. census. While it might look odd to members of our immediate family, I have decided to use the original spelling, Fragale, throughout this account. As for our pronunciation of the name, I had assumed that it was a peculiarity of the Escanaba family. I felt rather silly when Dolly, Angelo‘s daughter, told me that the Fragales in Pennsylvania pronounced it like we did.

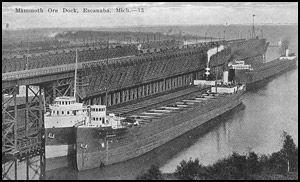

Upper Michigan in 1900Iron ore was discovered in the Upper Peninsula in the 1840's. You didn’t even have to dig for some of it: it was right there on the surface, and it had the perfect constituency for the Bessemer Steel process. Railroads were built to get the ore to lakes Superior and Michigan. Huge ore docks were constructed to transfer the ore from train to ship. To negotiate the twenty-one foot drop in water level out of Lake Superior, the first boat locks were opened at Sault Saint Marie in 1855, the famous Soo Locks. All of these steps, from mine to steel mill, were in states of constant upgrade: bigger ships; longer and larger docks; newer and larger locks. The ports along Lake Superior and Lake Michigan became very busy places. In 1888 a new international bridge opened next to the Soo Locks, and the Minneapolis, St. Paul and Sault Ste. Marie Railroad (the Soo Line) could now take grain, timber and passengers from the Dakotas all the way to Boston and Philadelphia. By 1893, Ashland, Wisconsin, was the second busiest port on the great lakes, The biggest bottleneck in the process, unloading the boats, was overcome with the invention of the Hulett Unloaders in 1898, gigantic machines spanning up to four railroad tracks and cantilevering far over the harbor. They scooped the ore out of the ship’s holds in huge gulps and cut unloading times by two thirds. By 1910 there were dozens of these machines in destination ports such as South Chicago in Illinois, Gary, in Indiana, and Cleveland and Lorain, in Ohio. There was a bustling little town a few dozen miles from Escanaba called Manistique, at the intersection of the famous Soo Line railroad and the newly built Manistique and Northwestern Railroad. A man named Elijah Westen had built the M&NW in 1896, intending to move both iron ore and lumber (the region’s other great industry) on the same line. Weston planned for ore to his Manistique ore works, hardwoods to power them, and softwoods for export. He operated a stone quarry, and had dreams of ferries across Lake Michigan. He died in 1898, and his grand schemes were never fully realized. Elijah Weston’s railroad survived - barely - and did carry lumber from the remote logging camps to Lake Michigan. The railroad underwent several ownership and name changes over the next decade, finally becoming the Manistique & Lake Superior, the M&LS, known locally as the Haywire, and to some as the Muck & Loon Shit. It was into this turn of the century environment that not one, but three Fragale immigrants arrived.

John, Angelo and MikeMike’s cousin, John Fragale, may have been the first person in his extended family to arrive in America. I’m assuming that he was born as Giovanni Fragale. The 1930 census says that he arrived in 1894. What drew him to Manistique, Michigan is anybody’s guess, but there were a lot of jobs in the area for immigrants, often in the lumber industry. What drew John to America itself might have been another story altogether. He was married in Italy, and had a daughter named Maria (Mary, when she later came to America). He probably had no plans of sending for his wife at some later date. According to Angelo’s daughter, Dolly, the family story was that John’s wife led a “risqué life,” and John probably came to America for both economic and social betterment. Maybe he just ran away. Whether he worked in the lumber industry is unknown, but by 1910 John Fragale described himself as a farmer, and the 1920 and 1930 census documents show the same occupation. Farming was about all that many of the Fragale immigrants knew from the old country. John lived in Thompson Township, just southeast of Manistique, with a French-Canadian woman named Agnes Savageau. They eventually had seven children, beginning in 1900 with the birth of daughter Irene Lucille Fragale, and followed in 1901 with son Albert. Next to come to America was Mike’s brother Angelo Fragale, although he was using his birth name Francesco at that time. Ellis Island documents show him arriving in the states in 1897. When he arrived in Upper Michigan is unknown, but Dolly believed that he lived there around the turn of the century. She said that he definitely worked in the lumber industry. Whether he lived with his cousin John is also unknown. Often, lumber men lived for extended periods in camps up north in the woods. Dolly told me that her father more than once mentioned Sault Ste. Marie at the Canadian border, so he definitely visited there, perhaps either on the way to Manistique, or while returning to the east coast. The new lock, the huge ships and the international bridge must have been awe-inspiring in 1900; they're impressive even today. Then came Mike. The 1920 census lists his arrival in America as 1900, but the 1930 census lists the year as 1902. In 1900, Mike’s brother-in-law, Serafino Leo, was working in eastern Pennsylvania, and by 1902, Mike’s sister Maria (Mary) and brother Antonio had joined him. It’s probable that Mike spent time in the Kennett Square vicinity before moving on to Upper Michigan. He obviously knew of his cousin up in Manistique, but exactly when he got there is uncertain. My guess is somewhere between 1901 and 1903. His obituary later reported that he arrived in Escanaba in 1903. Mike’s stay with John Fragale may have been short. There are two old stories told which come into play here. The first is from my grandmother Margaret Fragale-Williams. It seems that there was a tarp pulled over a well to keep the water from freezing, a dog which pulled the tarp off of the well, and a woman who then shot the dog dead. The woman would likely be Agnes, John Fragale’s wife. Margaret believed that this upset her father, a quiet and gentle man, enough to make him move on from Manistique. Mike’s daughter Irene told the other story, which was probably the bigger factor. Mike didn’t know that his cousin had a new family in Michigan until he got there, and was very upset to find out that John was a bigamist. While brother Angelo’s family had further contact with John for years after Angelo left Michigan, after Mike moved on to Escanaba he never talked to his cousin John again. It's sad that John’s daughter, Irene Lucille Fragale, and Mike’s daughter, Irene Ernestine Fragale, lived over a century apiece, yet they never met each other. Their fathers came from the same locale in Italy and were cousins, and these two women grew up about fifty miles apart. When I asked her, my great-aunt Irene had never even heard of the woman she had likely been named after.

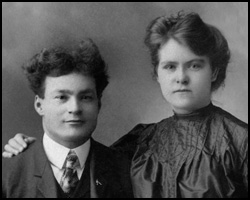

Emma Maria LeisnerBetween 1881 and 1885, two brothers and a sister all surnamed Giese, and two brothers I know nothing about their lives in the old country; the ships' manifests are the only documents from prior to the turn of the century. Children Carl and Maria Leisner probably died young. They aren't mentioned again anywhere else that I could find. Mike’s daughter Irene told a vague story about a sibling who had drowned after diving into shallow water, and that’s it. My mother was told that Emma Leisner was the only Leisner child born in America, but it turned out that her brother Ewald was also born here. How did Emma Leisner and Mike Fragale meet? Mom said that Emma worked in Escanaba as a household servant for a time, and here‘s an oft told family story: Emma was riding the carousel at the fairgrounds in Escanaba, and every time it circled around, a young Italian man bopped her with one of those paddleball toys, which I suppose he had bought right there at the fair. While Emma almost never smiled, I like to think that Mike got a smile out of her that day. Either way, on the fourth of March, 1908, Mike Fragale and Emma Leisner were married. They lived down in Ford River with the Leisners for a while, but Mike had a job on the ore docks, and soon they were living in Escanaba.

Irene, Harriet and MargaretMike and Emma named their first child Irene Ernestine Fragale. She was born in Ford River. The name Ernestine was definitely after Emma’s mother. I speculate that the name Irene came from the name of John Fragale’s first daughter. Mike may never have wanted to see John again, but the name Irene must have appealed to him. He certainly would have met her while staying in Manistique. Their second child was named Harriet Bertha Fragale. Bertha is easy to account for, since Emma had an older sister named Bertha. That story of Emma working as a household servant before her marriage included a young girl in the house who tragically took sick and died. That girl was named Harriet. The third child was my grandmother, Margaret Regina Fragale. The only known instance of the name Margaret in the family at that time was Mike’s sister Josephine’s daughter, Mary Margaret Citino, who had been born about two years earlier. The Escanaba Fragales had some German immigrant friends who lived for many years across the street named Hubert and Virginia Bubser. Virginia was godmother to Harriet and Margaret, and she was listed as Regina Bubser on the documents, possibly her middle name. There was a story which might have involved Mike’s desire for a son to carry on the Fragale name. This story was that Mike, upon learning that he had yet another daughter, got a bit inebriated and emotional, and comically tried to wrestle a baby carriage up the basement stairs.

427 South 18th StreetThe house was built in 1917, and Irene told me that it cost The Fragales had an upright piano, and Irene had a true talent for playing it. She studied piano for eleven years, but when they looked into professional lessons for her, the fee of fifty dollars per hour put an end to that. As I’ve said, Emma rarely smiled. Emma’s granddaughter Pat tells the story that near the end of her life, in 1982, Emma took Pat’s husband Wayne’s hand and gave him a big smile. A week or two later Emma was dead. Emma’s son-in-law Brendan used to say that Emma smiled like she had a.......well, we’ll leave what Brendan said for another time. In contrast , Mike Fragale was always smiling, and had a silly side. Irene told me that when her mother made doughnuts, her father would waltz around the house with one on each finger, eventually eating them all.. The Fragales also owned the corner lot next to the house. They never built on it, and It seems that the Fragale family had farming in their blood. Mike’s brothers and sisters out in Pennsylvania were all involved in growing things. The Kennett Square Fragales eventually specialized in mushrooms. Mike’s brother Louis and others grew Roses. Granddaughter Pat remembers that the back yard in Escanaba was Mike’s pride and joy. He filled that yard with flowers that he tended, gladiolas or irises or whatever. He often earned ribbons for them at the Escanaba Fair. Emma had a skill indoors with African Violets of all colors. Pat said that she thought that her grandma knew magic, starting new plants from fallen leaves.

Working on the RailroadMike worked on the railroad, on the massive ore docks in Escanaba, first for the Milwaukee Road, then for the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. He was a member of the Top Dock Ore Handlers Union, Local 400. In the 1910 census, Mike’s occupation is illegible to me, but in the following three censuses, he’s a “top dock worker,” a “freight handler” and an “ore dock worker,” likely all names for the same job. While I’m sure that seniority counted for something, it was still basic physical labor. Ore was dumped from the railroad cars into “pockets” high up over Lake Michigan, and when the ore ship was in position, large chutes, occasionally called spouts, were swung outward from the docks until the ends were in position over the cargo hatches on the ships. It seems that every other chute was deployed, so ore was dumped into the ship at twenty-four foot intervals. In a perfect world, gravity would do most of the work. But in practice, the ore could arrive as a wet or frozen-solid mass in the railroad cars, or become a wet or frozen-solid mass in the pockets. It would then be nasty work freeing up the ore, using sledges and long poles. After those pockets were emptied, the ship would be winched along the dock a number of dozens of feet, until different chutes could empty different pockets into the hold. Irene told me that her father would have to clean out the chutes on occasion. When Mike got home from work, he was often so filthy that Emma made him go straight to the basement to strip off his clothes before entering the rest of the house. Mike Fragale must have seen both the worst and best of times on the docks. During 1931 and 1932 (great depression years) there was a fifty percent drop in shipments. At the turn of the century there had been 500 or more men working for the Chicago & Northwestern railroad in Escanaba, out of a total population of 9000, and three decades later the numbers were similar. But in 1932 there were over a thousand men unemployed in town, most of them the sole wage earners for their families. It got so bad that the Milwaukee Road closed its two ore docks and transferred all of its business to the Chicago & Northwestern docks. The Milwaukee Road docks never really recovered, became neglected and were later demolished. By 1942, there had been a complete turnaround. The war effort resulted in the busiest years the ore docks had ever seen. Improvements were made in Escanaba because the United States was worried about German sabotage to the Soo Locks. Escanaba had held most of the ore shipment records anyway, since boats which didn’t have to go through the locks could carry heavier loads. Through all of these times, Mike Fragale rode to work each day on his bicycle.

Getting Around, Trips out East, and Learning the LanguageNeither Mike nor Emma had a car, or ever learned to drive. In those days you could still live that way. Escanaba is still a small city, but the little neighborhood grocery stores and such are now mostly gone. It also helped if you knew neighbors and friends who did have cars. The Fragales occasionally got out of town in the early days with one such neighbor couple, on day trips and picnics. In 1926 they took a real trip, however, to visit the Mike’s relatives in Pennsylvania. Mike had not seen many of these folks (if not all of them) for a quarter of a century. His job came with a railroad pass, a free ticket to just about anywhere the railroad went. Mike’s daughter Margaret later related how warmly the relatives out east embraced the family, actually running out of the house with open arms upon their arrival. It was quite a contrast to the staid habits of the German relatives in Upper Michigan. None of Mike’s relatives ever came to visit in Escanaba, though, and Irene told me that they never went out east again as a family. Mike and Emma did return to Kennett Square around 1950, but that appears to have been the only other time. I have photographic evidence that Mike’s niece, Lucie Leo, and her sister-in-law Mary visited Escanaba in the late 1950s, but I’m not certain who else might have been with them. Relatives in Pennsylvania remembered Margaret and her husband Brendan, and Harriet and Irene, from at least one other trip to Kennett Square. An interesting story came out of that 1926 trip. My grandmother Margaret told my mother that Mike had mostly lost the ability to converse in Italian. There had been no one who spoke it in Escanaba. My grandmother said that Mike had needed an interpreter to speak with his sister. Josephine Fragale-Citino’s daughter Helen told me that her mother managed to speak English well, so that leaves Mike’s other sister, Mary Fragale-Leo. Mary’s granddaughter Melania said that her grandfather Serafino Leo spoke English well enough to get along, but her father Archie Ruggieri really mastered the language. Perhaps Archie served as interpreter between Mike and Mary. Mike spoke in broken English, and he had learned it from a wife who had grown up with Germans, and I’m sure he picked up more than a bit on the ore dock. Someone gave Mike some remedial children’s grammar books at one point, but Emma took them away from him. Not that he swore a lot, and by all accounts he was a quiet man, but my mother distinctly remembers him invoking the names of certain religious figures, in Italian.

Ed, Brendan and DickThe three Fragale girls married three local Escanaba boys: Irene married Edward James Stratton, son of Edward Mitchell Stratton and Nora E. Mogan. Harriet married Leon Richard Schram who went by the name of Dick. He was an athlete in college, and competed in the pole vault at Marquette University, winning second place in the NCAA championships in Chicago. Dick hitchhiked from Escanaba to California in 1931 for the Olympic tryouts, since the Olympic committee did not have the money to pay his way. He lost seventeen pounds during the trip, and didn’t make the team. A fascinating figure from my childhood, Dick Schram also was a noted football and basketball referee, taught science in high school, and repaired black and white televisions and more in his basement. Margaret married Brendan Roger Williams, son of Roger Nicholas Williams and Leah Elizabeth Laviolette. Brendan was also an athlete, and he had starred on the high school football team with his brother Marlin. He won a scholarship to play football at Marquette University, but was forced to leave school early after a family member from the Williams side revealed to the Jesuits that he had married a Lutheran. Emma’s family was German Lutheran, but both Irene and Margaret converted to Catholicism when they married. Emma had never wanted Mike to go to the Catholic church. The Lutheran minister in town started his sermons with “Thank God you weren’t born a Roman Catholic!” Even Emma eventually stopped attending the services. Years later, on his death bed, Mike asked his daughter Irene to bring a priest so he could receive the sacrament of confession, and be reinstated in the church. Irene did as asked, and as far as I know, Emma never knew about it. When Emma herself was near the end of her life, she too sought out the Catholic Church, and was later allowed burial next to her husband..

609 South 18th Street, the War Years and BeyondThere was another house in the family, just down the street. It had started out From the early 1930's to about 1949, Irene and Ed rented 609 South 18th Street from Mike for twelve dollars per month. All four of the Stratton children were born while they lived there: Joan, Jim, Don and Pat, four of Mike and Emma’s eventual eight grandchildren. Brendan and Margaret rented a house one street over, at 427 S. 17th Street, until Brendan joined the army and left to fight in Europe. Margaret and her two children, Harriet (my Mom) and Mike, moved into the Fragale house until Brendan returned. There was a frightening time when they were notified that Brendan had been wounded in the war, because at first they were not given any details. It turned out that Brendan had been shot clean through the forearm, and he made a complete recovery. When Brendan Williams returned to Escanaba, he bought a house at 324 S. 17th Street. This was the house my mother grew up in, still only a two block walk from the Fragale house. These were fine years for the Fragales, with Irene and her family just down the street, Margaret and her family only a few blocks away, and Harriet and Dick renting a second floor apartment on Ludington Street, downtown. Pat said that the kids were always welcome visitors, met inside the back door with hugs. Grandma Fragale almost always had bananas in the fruit bowl. She pronounced it “banano,” which became a silly family tradition. Pat said that the kids would tear through the house in a circle: living room, dining room, spare bedroom, bathroom, bedroom and living room again. Grandpa Mike, wearing his usual suspenders and sitting in his usual chair would joke, in his broken English, “Stop that running, or I’ll cut off your feet!” My mother told me that one weekend morning she woke up hungry, and since her parents were still asleep, she roller skated over to her grandparents house with a frying pan and two eggs. Grandma Fragale did make her breakfast, and mom got into a small bit of trouble over it. Ed Stratton worked for the phone company, and from 1949 on he was transferred from here to there. First, about four years in Sault Ste. Marie, then a short time in Marquette, then three years in Menominee, then back to Marquette. They would often drive to Escanaba after moving out, occasions for Margaret, Harriet and Irene to convene a gabfest with their mother, seeming to all talk at the same time. Ed sought out chores to get away from the women. All the Stratton and Williams cousins would play, and often Irene and Harriet would perform duets on the piano. Pat remembers sometimes visiting alone by train, and when she was picked up at the station it might even be reported in the local newspaper. When the Strattons left Escanaba, Dick bought the house at 609 S. 18th Street from his father-in-law, Mike Fragale.

The Last DecadesAfter Brendan returned from the war, he and Margaret had two more children, Mary and Brendan Junior, giving Mike and Emma a total of eight grandchildren. In the mid 1950's, the Williams family built a new house on Lake Drive. Michael E. Fragale retired in 1953. Mike and Emma celebrated their golden wedding anniversary in 1958, and Mike died on June 2, 1960, at the age of 76. Emma lived alone at 427 S. 18th Street long after that, and was visited often by her children, grandchildren, and eventually great-grandchildren. Sometime in the late 1960's, possibly the early 1970's, Harriet and Dick had a falling out, ending in divorce. Harriet moved in with her mother Emma, and bought the Fragale House from her. Dick continued to live in the other house, and did so until his death in 2003. My family didn’t see Dick at all after the divorce, but Aunt Harriet and her mother certainly did. As I‘ve said, the Fragale house was near the end of the 400 block of 18th Street, with an empty lot next to it on the corner, and the 500 block had no houses on it at all. The house at 609 S. 18th was the second or third house from its corner, and while that house was not visible from where Emma and Harriet were, Harriet could see Dick come and go, or at least see whether or not his car was down there. I have to chuckle, thinking of those two old ladies in that house, with Harriet peering out of the oriel window in the dining room, keeping tabs on “Unk the Skunk.” Dick must have felt their eyes on him. Emma Maria Leisner-Fragale died in 1982, at the age of Harriet had willed the house to the two younger Williams children, Mary and Brendan Junior, her niece and nephew. Mary had died of complications from diabetes in 1980, so the house went to Brendan. He sold it in 1988, and that owner still lives there, as of 2014. He’s made many renovations, and the house will be in fine shape when it turns one hundred years old, in 2017. The house at 609 S. 18th street is now owned by the son of a woman that Dick lived with for twenty-five years after his divorce. After my grandmother Margaret Fragale-Williams died on June 13, 1986, there were no more Fragales in Escanaba, but up in Marquette, Irene Fragale-Stratton lived another quarter of a century, and died on September 14, 2012 at the age of 103. |

||||||